I don't wanna play: Why we should stop gamification

Gamification [mass noun]: the application of typical elements of game playing (e.g. point scoring, competition with others, rules of play) to other areas of activity, typically as an online marketing technique to encourage engagement with a product or service.

The Oxford Dictionary

Some days ago I updated my iPad Pro to the new iPadOS. Apart from using it for work, I do most of my reading on it. When you are a digital nomad, you cannot carry a lot of paperback books in your luggage.

How much time do you read per day? How many books a year?

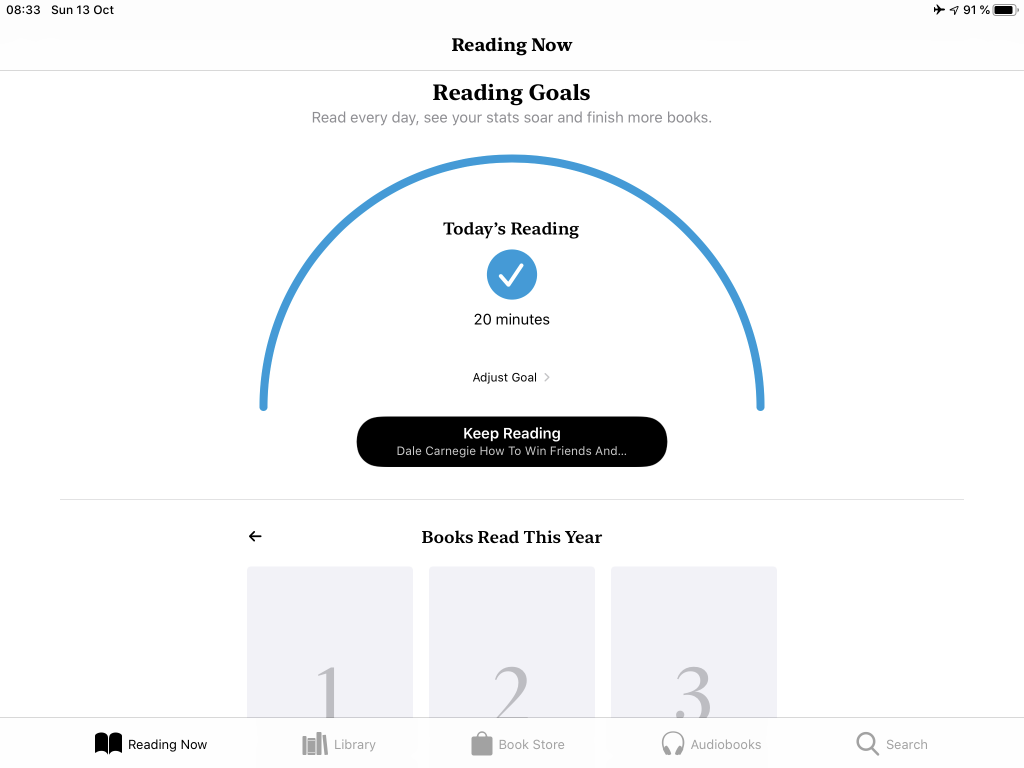

Then on Friday evening I had some free time so I decided to make tea and spend some time reading. After five minutes, a notification interrupted me, congratulating me for having reached my goal of reading five minutes that day.

What the … ?

In a completely anti-stoic burst of rage, I rushed to the Settings app until I located a way of disabling these notifications. I don’t want to be told how much time I should spend reading, Apple, thanks, but no, thanks.

Two years ago, a survey from Fast Company concluded that the average CEO reads 60 books a year. Immediately, there was a frenzy on the net, with articles explaining why that made them smarter and more successful, competitions on social media, and even an article on Inc showing you how you could also be like these CEOs and read 4-5 books per week.

Reading for me is a pleasure. I rarely read fiction, I usually read books that teach me something, like “How to be everything” or “The $100 Startup”. Still, reading for me is not about hoarding knowledge. It’s entertainment. I like to read books that add value to my life, but I don’t want to turn reading into a job.

I honestly don’t know how many books I read per year, and I don’t want to know either.

However, even though I didn’t receive these notifications anymore, every time I opened the Books app, I saw a screen with the time I’d spent reading that day, if I had or had not reached my (?) goals, and how many books I’d read per year. It took me some more time to find out how to disable this setting too.

Don’t you wanna play some more?

So what’s the problem with that? You may think it’s just a game, or an interesting way of encouraging yourself to read more, but it’s not.

It’s a way of deciding for you. And deciding in important aspects of your life, like how you spend your time.

Come on… just for reading one minute more?

The problem here is that when you spend reading one minute more than you intended that day, or you read one book more per year to reach your goal because the application suggested it, it’s not you who is deciding what to do with your time.

It’s an algorithm.

Multiply that by the number of apps gamifying your life for profit, such as Facebook, Youtube, Instagram, Snapchat, WhatsApp, or Google, and you realize that we are not talking about one minute here.

When you receive a notification from Facebook and you open the app on your mobile phone, who is deciding where you are going to spend the next two, ten or thirty minutes? Don’t be fooled, it’s not you. And you are not even conscious of how much time it’s going to be beforehand.

And the sad thing is that it’s not even somebody else the one deciding for you. It’s an algorithm. One that has been designed to maximize the time you spend on that application, whatever it takes.

Unfortunately, the problem is not only how that algorithms decide how you spend your time, it’s also how they segment society at a bigger scale.

Algorithm-driven segmentation of society

Imagine that Apple Books decided one day to set your default reading goal depending on your profile, so if you are a CEO you are suggested one hour of reading a day and sixty books per year, and if you are a construction worker you are OK with five minutes of daily reading and three books per year.

If that does not sound really bad to you, you’ve never read “Brave new world” by Aldous Huxley.

It’s no secret that social media and platforms such as Netflix or Youtube display different information to different users. This information is based on your profile, the things you have chosen or visited previously, and other data that they have gathered about you from other sources. To put it in other words, the information you see on Google, Facebook, Netflix or Youtube has nothing to do with the information served to your brother or girlfriend.

Thus, we are violating one of the essential principles of the internet, which is the access to free, objective and untampered information. Imagine if the Wikipedia showed different results about evolution to creationists and non-religious visitors.

This may not sound like a big deal right? If I like basketball, why not showing me basketball movies, basketball books, basketball events?

But this segmentation of our society has consequences. It can be exploited for profit, or political interests. The manipulation of the US elections and the Brexit campaign via Facebook thanks to Cambridge Analytica were the most prominent and recent examples.

Polarization

But it’s not just our segmentation into exploitable groups what worries me, it’s the polarization of our opinions due to this segmentation of information.

Polarization means manipulating the opinions of the population so they lean toward a radical stance. Reasonable opinions are not good for these algorithms. They do not generate engagement. It’s when you passionately defend a point of view that you click on that next video Youtube is offering you.

And all it takes to start this process of radicalization is a single click. That click means the algorithm will infer you are interested in that stuff, and show you more of it. As you keep on making “choices” –that are not really choices– and clicking further, the algorithm decides what content to serve you next. If you repeat that process long enough, you can influence this person.

Que Viva España!

You may think this is an exaggeration, but it’s not. In Spain, there’s one traditional song called “Que Viva España” (Long live Spain!). One of these old songs about how Spain is the best country in the world, the most beautiful, blah blah blah. Due to the Spanish history and how our society polarized after the civil war, this song is frequently associated to right-wing people in Spain.

One day, my husband, her sister and I were talking about Spanish food. All of us live outside of Spain, and they were arguing that the Spanish food was the best in the world. As a joke, I looked for this song on Youtube and played it out loud. We all had a good laugh.

But after that day, for months, Youtube kept on suggesting me videos about Franco (the Spanish dictator) or far-right political parties. Thankfully, I disabled autoplay early on.

That’s scary. I don’t click on these links, but what if I was a young and influenceable Spanish teenager?

Look at your facebook newsfeed. You are not seeing all the posts and status updates of your friends. Facebook features some of them and hides others based on what it thinks you may agree with, or even strongly disagree with, if the algorithm decides that it will make you click and stay longer.

Let’s stop gamification

The European GDPR was a remarkable step in the right direction to protect the privacy of the European citizens. One of its main precepts is that you should explicitly opt in to the use of your data by third parties. In other words, you need to say: “Yes, I do want my data to be used by you so you can profile me, send me promotional information or keep my information for your own interests”.

However, we still have a long path ahead. If a company like Apple, perceived as one of the most privacy-savvy companies in the world, has started to use these techniques too, we are going in the wrong direction.

We need to protect the universality of information and our right to decide what we want to do with our time. We have become the new digital product of the XXI century. Our time, our attention, and our information are the product, not just our money anymore.

So I might be overreacting, but I don’t want to be told how much time I should read every day, not by a single minute. I don’t want Netflix or Youtube to autoplay the next video for me. I want to decide how much time I spend in front of a screen. And if I need to look for books to read, or videos to watch next, I know where to look for them.

Conclusion

Gamification is everywhere these days. It’s been accepted in our society as something good. It is a tool to let you know which music you would like to hear next, or which video you should watch after this one.

But these suggestions come with a price tag, namely, losing our freedom to decide and handing over our time to algorithms that want you to spend as much time in their applications as possible.

Maybe like the character of a Brave New World, I am just claiming for my right to be unhappy in this perfectly happy world of gamification.

Comments ()