Why losing 130,000€ made me the happiest man alive (Part 2)

Welcome to the second part of the post series “Why losing 130,000€ made me the happiest man alive”! For those of you who missed the first part, in these articles I describe how I amended the biggest mistake of my youth (buying a house). Cue the dramatic intro music…

It took him more than a decade, but finally, after working his ass off to have a profitable business, our wiser (and unfortunately older) micropreneur was able to reap some of the benefits of his hard work to cancel out his mortgage, sell his house, and finally cut ties with Spain. Good riddance, traditional banks! Adios, grey offices! Au revoir, countries, flags, and borders! Welcome, freedom! Welc… scraaaaaaaaatch!

… Well, not so fast. Let me guide you through the nightmarish process of paying off my mortgage, selling my house, and closing my bank account.

… When plans refuse to come together

Well, as I mentioned, the plan was easy. After completing the annual report and deciding that I would be distributing 95,000€ in dividends (enough to cancel the remaining balance of my mortgage of 95,137€), this was roughly the plan:

- I would transfer 95,000€ to my Bankia account (my bank in Spain, the only account I still had because of the mortgage).

- Then I would cancel the mortgage (I was hoping it was something you could do online, or at least through a phone call)

- Next, I would put my house on sale for the real market value (which was roughly around 60-80k for a house like mine) to ensure a fast sale.

- Finally, I would get my money out of my Spanish account and into Revolut, and cancel the account for good.

Sounds easy, right? (every plan in which you have the cash does). Well, there was a problem.

I had not been a tax resident in Spain, or anywhere else for that matter, in years. That means I had no way of proving my tax residence.

And that is a problem. Those archaic institutions we usually call “banks” have a hard time understanding the concept of “not having a tax residence”. When I left Spain, I went through a hell of a process trying to explain to the gentlemen at ING Direct that I was no gangsta laundering money. I didn’t want to repeat that experience.

I knew I needed to show them something. Some proof of residence.

That weird guy that lives in Latvia and has a company in Estonia and a bank account in Lithuania…

Fortunately, I still had a valid Latvian resident ID. That was the country where I first landed after leaving Spain. Even though I never stayed there for long, or ever used any social benefits or public services there to be considered a real resident (let alone a tax resident), that’s where I officially was for Spain. And I had an ID to prove it. That was the closest to my real situation that the Spanish administration was able to get.

So I “just” needed to set my tax residence (which appeared as “undefined” in the bank’s atrocious interface) to Latvia. That apparently easy task turned out to be a complete nightmare. It took me more than four months. Bankia’s user interface didn’t help. Every single time I had to do something on the web, it failed. A tax residence in another European country? Too much for the web interface of a Spanish traditional bank.

For the bank’s representative, I was that weird guy residing in Latvia that had a company in Estonia and wanted to sell his house in Spain and send all his money to a Lithuanian bank account (Disclaimer: I don’t even live in any of these countries 😅). It would have been fairly comical if it hadn’t been that frustrating. This is a list of some of the things that went wrong during the process:

- The UI won’t let you choose any valid document to prove your tax residence in a foreign country.

- I had to submit my Latvian ID and the rental agreement (that had expired 5 years ago), alongside the declaration of dividends, the entry in the registry, and articles of associations of the company, and the last tax report submitted to the Spanish authorities years and years and years ago, among other things. They still didn’t want to believe me.

- The web interface was so bad, even the bank’s representative was not able to do certain things, like changing the country of my tax residence or accepting the CRS agreement.

- The process involved waiting for the bank to check all these documents, sometimes for weeks.

- Initially, the bank’s representative set my tax residence in Estonia instead of Latvia (because the company was Estonian), which caused the anti-money laundering department to block my account for weeks, as I had given them documents from Latvia (uh, oh! Is this guy part of some Eastern European mafia? Where in Russia is Latvia anyway?).

- I had to communicate with the bank’s support agent through an in-house chat that didn’t have notifications, so I needed to check the chat for updates several times per day. For four months. Good luck trying to have a productive morning.

A tortuous journey to pay my mortgage

Finally, after those four months, I was able to transfer the dividends to my Spanish bank account. Now, I “just” needed to cancel the mortgage with that money. I crossed my fingers and braced for the worst.

As expected, the “automatic” system for canceling the mortgage didn’t work at all. First, it tried to apply a cancelation fee of 1% (I know, it’s just 1000€, but as we will see later, I was already being stolen money from all fronts). So back to the chat. It took “just” a couple of weeks for the bank to fix the situation.

Then, being assured everything was ready, I clicked on “Pay off”, verified that the fee was 0%… and Bum! My account was frozen again and set to “simulation mode” (???). Some agonizing chat conversations later, I asked the bank, in not so friendly terms, to cancel my mortgage themselves.

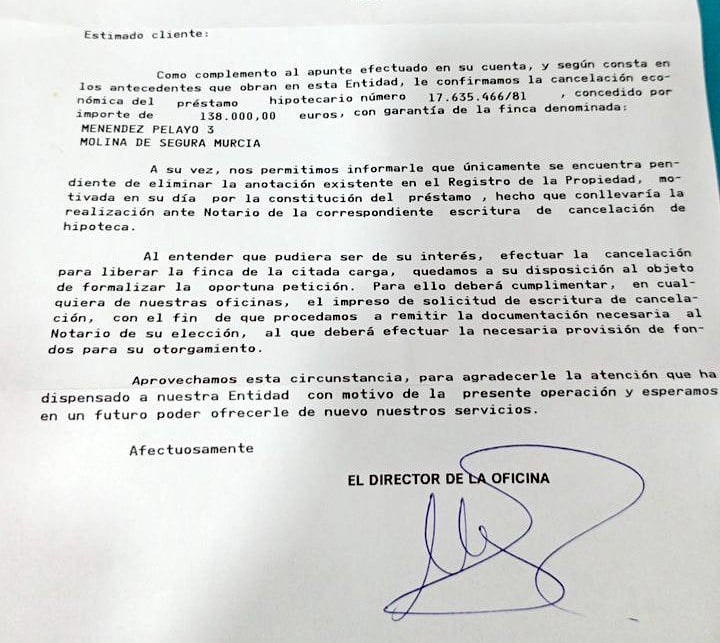

I literally cried when I received the confirmation from the bank stating that my mortgage had been canceled.

I was free! Well, not yet. I needed to sell the house and close the bank account.

Listing the house at a ridiculously low price

I took the market’s temperature and it was cold, very cold. I wondered if the patient was even alive. More than a decade after the real estate bubble explosion, and the financial crisis, for a house like mine (one street away from the town hall, so couldn’t be more centric, 100m², 3 rooms, elevator, terrace…), I would have been lucky to sell it for 80-85k. I decided to list it at 75k, and go down to 70k if needed.

That was a good strategy. Some days later, I had my first offer, and after two weeks, a couple decided to buy the house. So far so good.

Some people may wonder why I chose such a ridiculously low price. I had paid 138,000€ for the house, so I was selling it for half that money. Yes, I agree. It definitely seemed like a bad decision. In the last part of the series, I will argue the contrary. My goal was to get rid of the house as soon as possible. I would rather have funds to invest than a dead liability, even if I would lose money initially.

Of course, selling the house is easier said than done. There is a lot of stuff that you need to do. Again, being a nomad was an important drawback, alongside the fact that I was not in Spain. The lawyer helped, but only marginally, I still had to figure out a lot of things myself.

There’s no way around it. If you want to sell your house, you have to enter the kingdom of bureaucracy and become a puppet, dancing the red tape dance while hundred of hands pull the strings: bankers, notaries, local institutions, the tax office, engineers and auditors…

There is a whole parasitic society feeding off the poor souls who dare to enter the system, but I will discuss that in part three, where I also talk about the overall costs, some disgusting surprises, and the precautions I had to take to avoid problems with the Spanish Tax Office (which of course means more money).

A shocking number and a lesson learned

For now, I will conclude with a shocking number and a lesson learned. The number is 60,000€. That’s the amount of money I had left after paying all the costs, banking commissions, notary fees, and other expenses. From a sale value of 70,000€, that’s more than a 14% loss.

The lesson learned for me was: don’t get into the system again. I took the red pill, and I’m glad to be out of Matrix. I currently live in an Airbnb apartment. That means I don’t have to worry about electricity, heating, internet, or water bills, and I am paying half the rent I was paying in Madrid. If I want to move, I can just pack up my things and leave. I have all my money in online banks. I can manage my company completely online. I don’t have to put up with any government or institution. I basically don’t exist for them. And I couldn’t be happier.

Yes, this has some drawbacks. I have no parental nation-state to patronize me. I have to take care of my health insurance, pension, and other stuff most people take for granted. I have to be responsible for my life. But that’s both a small price to pay and –the more I think about it, the more I am sure– a blessing.

I’m not trying to put together a manifesto here or trying to convince anybody of anything. This is just an expression of pure joy, a shout of life, a story of pure happiness in 1791 words.

Birds flying high, you know how I feel…

Nina Simone, Feeling Good, from the “I put a spell on you” album.

Sun in the sky, you know how I feel…

Breeze driftin’ on by, you know how I feel.

It’s a new dawn, it’s a new day, it’s a new life for me… (oh yeah)

It’s a new dawn, it’s a new day, it’s a new life for me…

… And I’m feeling good.

In part three I will show all the numbers and defend why I think selling was the right decision, not only from a personal (psychological, spiritual, emotional) perspective, but also from a financial point of view. See you there!

Comments ()