Demystifying Digital Nomad Taxes

One of the most disturbing and frightening topics for aspiring digital nomads is how to pay their taxes. In this post, I try to demystify digital nomad taxes, where and how to pay them and offer some insights on the topic.

Currently, my partner and I live as digital nomads, managing our Estonian companies thanks to the e-Residency program. Furthermore, we are living in Latvia, and even though we will be spending some time there, we plan on moving regularly. We are from Spain, so originally we were paying our taxes there as freelancers.

Sounds complicated, right?

When I decided to become a digital nomad, the question that kept me awake for so many nights was paying my taxes. I wanted to do this right. I pictured myself in jail, accused of violating hundreds of tax laws and international regulations I couldn’t even understand, and fined for an amount I wouldn’t be able to pay in my whole life…

Turns out, it’s a complex topic, but you can certainly do it right once you understand some basic rules.

Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer. This post is merely based on my research and experience. However, this article should never replace legal advice from a professional applied to your specific situation.

Digital Nomad Taxes: The basics

Before getting started, you need to have some concepts clear, namely the difference between residency and citizenship, and the different types of tax regulations.

Residency VS Citizenship

Your citizenship is usually established when you are born, or you become an adult. It rarely changes, unless you are under special circumstances -like if your parents are from different countries- or you deliberately change it.

In a way, it defines your home country. Traveling or moving to a different country, even permanently, won’t have any effect on it, you will still be a citizen of your home country.

There are ways of acquiring a new citizenship or changing your current one. However, it’s not something that happens just by traveling or visiting other countries.

Conversely, your residency defines where you are living or spending most of your time. Under certain circumstances, you can become a resident of another country. For example, if you are European, and move to another country, maybe to work, for a year, you can certainly become a resident there. As we will see later, this has implications in where you should pay your taxes.

All in all, changing your residency is way easier than changing your citizenship.

Citizenship and residency give you different rights and duties. Let’s see how this affects how you should pay taxes, depending on the tax regulation you are under.

Types of Tax Regulations

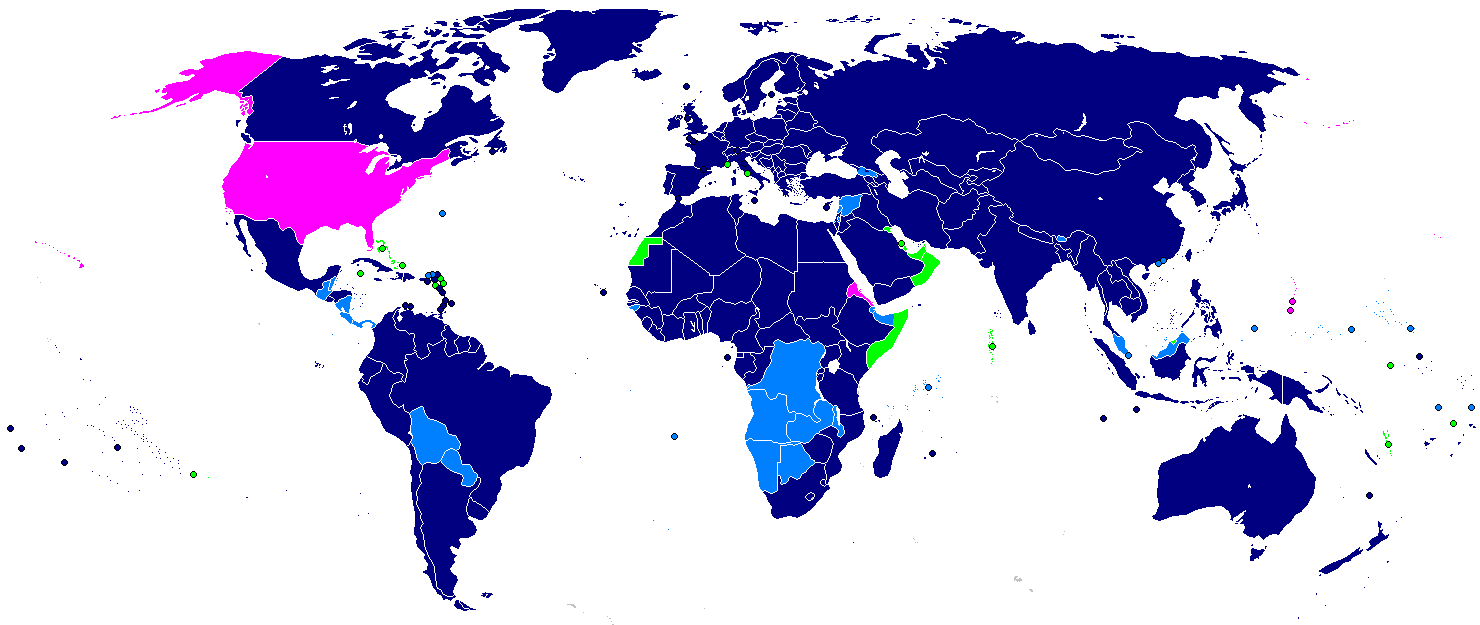

Different countries apply different regulations to how their citizens pay taxes.

Most countries apply a Residence-based Tax Regulation. This means that you, as an individual, pay taxes in your country of residence, not necessarily your home country. All European countries adhere to this regulation system.

Under most circumstances, you are considered resident of the country where you spend more than half of the year. We’ll talk about this later in detail.

Other countries, like the US and Eritrea, apply a Citizenship-based Tax Regulation. These countries tax their citizens no matter where they are. This implies that if you are a US citizen, even if you go to France to live and work there for a French company for 3 years, you will still have to pay your taxes in America.

The US tax system is very complex and there are lots of patches and exceptions to this rule, but generally speaking, citizenship-based tax countries will tax their nonresident citizens on worldwide income.

There are other more interesting tax regulations. Territorial tax regulation systems -like Panama- tax their individual citizens only on their local income. This means that if you earn money overseas, that’s not taxed. Finally, there are a few countries that impose no taxes on individuals, like Qatar or the Cayman Islands. These countries are usually considered tax havens, and the implications of being a resident or citizen of those countries are too complex to explore in this article.

Of course, there are lots of exceptions and special cases on every concrete legislation. For example, if you are a British student paying back student loans, the UK will impose a global income tax on them, no matter where you live. To better understand your particular case, you should ask a professional.

Double Taxation Treaties

There are no international rules that say how those who work or spend time outside their home countries are to be taxed on their income.

In some cases, two countries could consider you a tax-resident at the same time, and both could require you to pay taxes on your total worldwide income.

Luckily, most countries have double tax agreements, that usually provide the rules that determine which country should treat you as a resident and, consequently, tax you as an individual.

In the European Union, for instance, there’s a list of double-taxation treaties with other countries. If you are a European citizen, it’s worth checking it out.

You are NOT Your Company

One of the most confusing aspects of running a company is the distinction between you and your company regarding taxes. Thus, there’s one thing that needs to be clear in your mind.

You are not your company.

This distinction is especially important when it comes to taxes. Indeed, when your company generates revenue, this money belongs to the company. You cannot simply use this money for your personal affairs. The company will, depending on the country of incorporation, need to pay or not taxes related to that income.

Then, eventually, you get some money out of your company bank account and into your personal one. There are many ways of doing that, like assigning yourself a salary or paying dividends. Whatever the case, at that very moment, you earn some money as an individual, and are responsible for declaring it for tax purposes. Additionally, in this process, the company may be liable for paying some extra taxes when it gives money to an employee, founder or service provider.

Note that your company may pay taxes in a completely different jurisdiction than you. As an example, imagine you are a micropreneur with an Estonian company. Now and again, you pay yourself a salary from your own company, transferring the money from your Estonian account to your German personal one. Then, your Estonian company must pay some taxes for this salary, of course, to the Estonian authorities. On the other hand, when you do your yearly tax return in Germany, you will need to pay the corresponding amount of taxes for the money you (as an employee) earned to the German authorities.

For a more concrete example, have a look at the salary example from this post.

The problem with Current Tax Regulations and Digital Nomads

The world is not ready yet for digital nomads.

We are slowly getting there, in my opinion. However, right now, the concept of “not belonging” to a place or not having a steady residence completely clashes with most tax regulations. Countries are not ready for this kind of lifestyle, and obviously, your home country and any other place where you spend enough time will want to get money from you in form of taxes.

To make things worse, there’s no international law regarding taxes for digital nomads. Current laws were written in the times when people usually stayed in their home countries. Traveling the world on a regular basis presents many challenges that have no answer as of today.

Additionally, there are many things that are still tied to either your citizenship or your permanent residency. Some of these things include health insurance, contracts, work regulations, marriage rights, etc.

My hope is that, as the world evolves and the digital nomad lifestyle becomes more popular and understood, things will change. Some kind of international regulation will be needed for the citizens of the XXI century.

Digital Nomad Taxes: Rule Of Thumb

Unless you are a US citizen or are subject to a non-residence tax regulation, there’s an easy way to know where you should pay your taxes. You are considered resident of the country where you spend 183 days or more a year. This includes holidays, business and pleasure trips, and prolonged stays.

However, you don’t become a resident automatically by just living 183 days a year in a different country. Unless you explicitly say so, your home country would like to keep on considering you a resident there. Obviously. They want your money.

Depending on the legislation in your home country, you will need to communicate that your tax residency is somewhere else.

In the case of Spain, for example, once you travel to your destination country to stay there for more than 6 months, you need to fill a form (the 030 form) to indicate that you no longer are a Spanish resident. In this form, you give details about where you plan on becoming a tax resident.

Once you do that, you have to make sure to actually make this tax residence effective. There are many ways of doing that. One of them is earning a salary. Nevertheless, there are many other ways of paying a small amount of taxes, enough to justify your residency. Some of them include owning stocks, buying or renting properties, opening a company or performing other economic activity that might be subject to taxation.

If you don’t perform any of these actions, it’s still possible that your home country may want to consider you a tax resident there. Make sure to do your homework when traveling abroad.

Thus, the rule of thumb: you are resident of the country where you spend most of your time yearly, but it’s not an automatic process.

Taxes For Estonian e-Residents Owning A Company In Estonia

In this post, I explain in detail how to pay your VAT and taxes if you own a company in Estonia. Being one of my main concerns before opening mine, I know it’s certainly an interesting topic.

Digital Nomad Taxes: Avoiding Taxes?

A very common question related to digital nomads and paying taxes is:

If you travel the world regularly, never staying for more than six months in the same place, is it possible to become a no-tax resident for any country, thus avoiding taxes?

The answer is: yes, in theory. The 183 days rule specifies that you become a resident of the country where you spend 183 days or more on a year. As a result, you could spend up to three months on a place before traveling somewhere else, avoiding becoming a resident of any country.

While this is true, becoming a non-resident is not an easy process, and has many caveats. Unless you become a non-resident in your home country first, you will be considered a de-facto resident there. I talk about this rule and how to avoid taxes legally in this article.

Conclusion

In this article, I tried to demystify digital nomad taxes, and explain how to pay your taxes if you are working remotely while traveling the world on a regular basis.

While this is not an easy subject, once you have some concepts clear, it’s not that hard to figure out where and how to pay your taxes. Two main concepts to have in mind is the type of tax regulation you are under and the rule of the 183 days. I hope I helped you avoid some headaches.

Do you have a concrete question about where to pay your taxes, or about the different tax regulations or the difference between you (as a company) and you (as an employee)? Don’t hesitate to share it with us in the comments below.

Comments ()