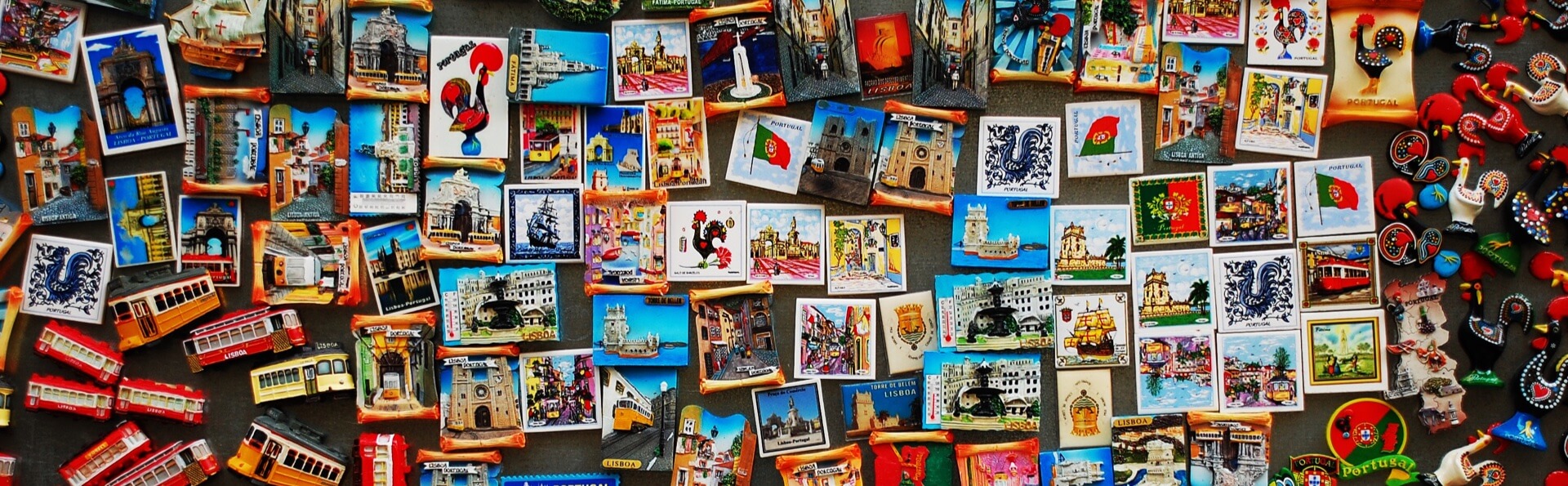

How To Avoid Taxes Legally: The 183 Days Rule [Updated 2022]

![How To Avoid Taxes Legally: The 183 Days Rule [Updated 2022]](/content/images/size/w1200/wordpress/2018/01/IMG_20190726_125241.jpg)

On my previous post, Demystifying Digital Nomad Taxes, I mentioned that there’s a way to avoid taxes legally if you are a digital nomad, by adhering to the 183 days rule.

Isn’t that illegal or morally wrong?

Talking about this topic in the context of digital nomadism is always subject to misunderstandings and uninformed criticism. Permanent travelers who don’t live and pay their taxes in any specific country are always judged as if they were doing something illegal or unethical. While that may be the case when people benefit from the social services of a country without contributing to its society (which I agree it’s not only illegal but totally wrong), in this post I am discussing a totally different thing.

True digital nomads, i.e: people without a tax residence permanently traveling the world, don’t enjoy social benefits from their home countries, or any other country for that matter. Much like a tourist, they don’t have access to public healthcare, the education system, public pension funds, or any social benefit others take for granted.

When criticizing them, most people ignore the fact that we have to pay for all these services. As I argue later in this post then, it is not only legal, but totally ok to not pay taxes anywhere if you are not using (and thus not abusing) social benefits in any country.

But first, let’s start our discussion by refreshing some basic concepts: residence based taxation and the 183 days rule.

Residence Based Taxation Systems And The 183 Days Rule

As I discussed in my previous post about taxes, there are different types of taxation systems.

Most countries apply a Residence-based Taxation. This means that you, as an individual, pay taxes in the country where you have your residence, not necessarily your home country.

All European countries adhere to this taxation system. Most civilized countries -with the exception of the US- do, in fact.

How do you determine your country of residence?

Easy. It’s the country where you spend most of the year, concretely, at least 183 days a year. While some countries may show small differences to how they apply this rule, it is a de-facto standard in all countries with residence-based taxation.

What If You Don’t Spend More Than 183 Days Anywhere?

As a result, if you travel regularly, never spending more than six months a year in the same country, you have no official residence. Does that mean that, in that case, you are not required to pay taxes in any country?

Well, if you are a citizen of a country that applies Residence-based Taxation, yes, that’s right.

Take into account that this applies to your personal taxes, not the taxes of your company. If you, like me, are an e-resident with a company in Estonia, your company will normally pay taxes there.

As we will see next, there are still some details you need to take into account. Let’s talk about them first before entering into legal and ethical considerations.

What If My Country Applies A Different Taxation System?

If you are a US citizen, things will be a lot harder for you. Only two countries in the world (Eritrea and the US) apply a Citizenship-based Taxation System.

If that’s your case, most of the stuff I discuss in this article unfortunately doesn’t apply to you. In order to break free from the chains of your nationality, you need to get a second passport, and then give up your American citizenship. So much for the land of the free. That discussion, I am afraid, is out of the scope of this post.

How To Avoid Taxes Legally

If you are reading this, I hope you are asking the right questions. This is not a post to show you how to avoid taxes by traveling the world. That woud be laughable. My goal is showing you how, if you are a nomad, you can avoid taxes legally based on the fact that you are not enjoying any benefits from them.

This is not as simple as buying a flight ticket and forgetting about your tax obligations. You want to do things right.

If you are a nomad, despite the fact that you have been traveling for years, your home country can still consider you a de-facto tax resident there. Even if you no longer spend a single day within its frontiers.

Obviously, if you have a business, you need to set your company in a modern country that offers you location independence and freedom to live anywhere in the world.

These are the steps you should be following if you want to confidently say goodbye to taxes while sleeping well at night. However, I am no accountant or lawyer, so if in doubt, my advice is to consult a local tax advisor.

Stop Being a Tax Resident At Your Home Country

First, it’s important to know that few countries understand concepts such as modern nomadism or location independence. Many of them expect you to have a tax residence somewhere. Otherwise, they assume you are a criminal trying to avoid taxes.

If you are a citizen of one of these nations, you will need to spend some time in a second country and, optionally, become a temporary resident there. In order to do that, you need to inform your home country that you are going to move to another country. How do you do that?

The first step is going to a country where you can stay for three to six months comfortably. When you get to this second country, head to your embassy and inform them that you are going to reside in this second country mid-term (if they ask for how long, vaguely indicate from six months to one year).

Then, you also need to inform the Tax Office of your home country that you going to stop being a tax resident there. The procedure for doing this varies from country to country. Germans are lucky, their government offers a form where they can indicate the fact that they are officially leaving Germany. In my case, as a Spaniard, I had to wait for six months and one day and then submit what’s called the 030 form to the tax office. Expect a lot of paperwork and being asked about your reasons for leaving the country. No presumption of innocence here.

Make Effective Your New Tax Residency

Ideally, you need to spend at least six months and a day in this second country. Enough for your home country to not consider you a tax resident according to the law. Take into account that you need to be able to legally reside in that country long enough to do so.

In some extreme cases, you may need to become a tax resident in your second country and pay taxes there at least once. Then, once you can explicitly prove to your home country that you are a tax resident somewhere else, you would be free to leave your second country (after de-registering as a resident there, of course).

How do you become a tax resident in that second country? Usually by registering as a resident in the immigration office and doing something that requires you to pay taxes.

Working for a local company and earning a salary is the most usual way of doing this. However, there are other ways, like owning stocks, investing in real estate, opening a business or co-founding a company. Consult a local tax advisor.

You don’t even need to actually pay a big amount of taxes. You just need to submit a tax report.

Be Careful Not To Choose A Tax Haven

Most residence-based tax countries are wary of tax havens and impose severe restrictions if you move your residency to such places.

Thus, for this initial country, don’t choose a tax haven. Choose a country with a good fiscal reputation, like a European country.

Take into account that these restrictions sometimes last for three years or more. In most European countries, you will still be considered a tax resident in your home country if you don’t spend at least the first three years outside of a tax haven.

Avoid Having “Important Economic Interests” In Any Country

In most Residence-based Taxation systems, there are other conditions under which you may be considered a tax resident. One of the most usual ones, apart from the 183 days rule, is having “important economic interests” in the country.

What does this mean?

Basically, if the majority of your wealth, businesses or money sources are located in a country, you are supposed to have a strong link to it.

Similarly, if your husband, wife or underage children are tax residents somewhere, that country can decide that you are a tax resident too. That makes sense, how can you say you are not a tax resident in Italy if your wife and children live there? Don’t you live with them?

Thus, make sure to sever all ties to your home country.

If you have a partner or a family, this is an important decision that you must make together.

Although not mandatory, I’d recommended not having real estate or other important properties in your home country either. Nothing that could be used against you by your tax office. You are a nomad after all, so that makes sense, right?

The Freedom Of Not Being Tax-Resident Anywhere

Once you have spent enough time in your second country, and have optionally made your tax residency effective, you are ready to go. Leave that place and move somewhere else.

Even if you had to become a tax resident in that other nation, it will be much easier to cancel your tax residency. This other estate, not being your home country, will rarely consider you a de-facto resident.

Make sure you are no longer considered a resident in any of these two places. From that moment on, you won’t need to pay personal taxes as long as you spend less than six months a year on a concrete country.

As I will explain next, one of the misconceptions of digital nomadism is that everything is advantages. You don’t pay taxes, so you can live completely carefree. Far from that, not being a tax resident has many caveats, and you need to understand them and take care of some of the things that you used to take for granted before.

Caveats

Not everything is a bed of roses when you are a permanent traveler, though. This is the point most people usually miss. Let’s talk about some of the caveats you need to be aware of.

Banks

Some days after I handed over the 030 form to my tax office, I received an email from my Spanish bank, ING Direct. The tone of the email was very demanding, even aggressive. They urged me to update my personal information and tax residence, and to send them a proof of address, such as a utility bill.

That caused me a lot of stress. I had a hard time making sure they wouldn’t close my account or freeze my funds before I could find another banking solution.

You will have to get used to the fact that banks expect you to live in one (and only one) country. They are mostly obsolete institutions from times when people rarely (if at all) left their homes or traveled regularly.

Fortunately, thanks to the digital banking revolution, there are many alternatives to traditional banks for digital nomads, such as Revolut, Wise, or N26 to name a few.

I managed to get rid of all my traditional bank accounts and I use digital banking solutions only for my personal finances.

Social Security And Other Social Benefits

If you live in a civilized country -with the exception of the US-, you are used to some social benefits, such as public healthcare and free health insurance.

Most of those social benefits are residence-based. And rightly so. They work on a solidarity basis. Peoply pay taxes to enjoy them. If you are no longer a tax resident in any country, you shouldn’t expect to benefit from free healthcare or other social services.

The European website for the Social Security Cover Abroad fails to address the situation of digital nomads without residence doing freelancing job or being self-employed by their companies.

Interestingly enough, if you own a company in Estonia as an e-Resident, and pay yourself a salary in Estonia (that includes social tax), you may be eligible to benefit from social security in Estonia:

If you are employed but have no substantial activity in your country of residence, you are covered where your employer’s head office or business is located.

Generally speaking, though, you will lose your social security benefits. If you are an EU citizen, you may get the European Union Social Security Card to be covered in Europe, but that’s hacking the system, it only works in the EU, and just for a couple of years.

If you want to be a nomad, be responsible with your choices and live by them. Take responsibility and get private health insurance. I can’t stress how important it is to be responsible about your health insurance and have coverage in case things go wrong.

Your Pension

Another important thing to consider. If you don’t pay taxes, you are not contributing to your pension. Hence, you will have to contribute to a pension scheme on your own.

Most young nomads I’ve spoken with didn’t believe their governments could guarantee their pensions before leaving their countries. I didn’t either. But even if you did, now that you are a nomad, you are on your own. Even if you are in your twenties now, and your pension is the last of your worries, start saving and investing early on. It’s never too early.

There are plenty of options, including private pension schemes, investing in passive income, stocks, P2P lending, real estate, and bonds. Plan ahead of time, your future self will thank you for it.

Legal And Ethical Considerations

As I mentioned earlier, any discussion involving taxes is subject to heated argument. If we are talking about an individual who is enjoying all the social benefits from a society without contributing to them, I think we all agree that this is wrong.

In the context of digital nomadism, though, I argue that it is perfectly ethical and legal. Let me elaborate on that.

Is It Ethical?

In most modern societies, its citizens pay taxes to enjoy social benefits in exchange. These benefits usually work on a solidarity basis. This means that you pay taxes so that your neighbor’s children get high quality education for free. Conversely, your neighbor pays taxes so that when you are ill, you get free access to public healthcare -unless you live in the US, of course-.

In the context of digital nomads, though, those arguments usually don’t apply. Why? Simple because you are not making use of these social benefits. You actually have to pay for these services to private companies.

Your children don’t go to public schools. If you are not a resident, you are not covered by the public healthcare system either. You need private health insurance, so you are not abusing the country’s social security. Also, you are not contributing to your pension, so the government will not pay you anything when you retire.

Also, you probably don’t have a car, so you are not using the public infrastructures and when you do -at a taxi or bus-, you pay for that service (inc. taxes).

Without enjoying those services, you are basically a long-term tourist. Would you ask a tourist to pay taxes yearly for your roads, your public schools, or hospitals, even if she does not use them?

So yes, I believe it is perfectly ethical.

Is It Legal?

Legal considerations are also important. Does a nation state have the right to own you just because you were born there? Are you bound to pay taxes in this country forever? Even if countries have the monopoly on violence, I believe in the ultimate freedom of the individual to choose where (and how) she wants to live.

But is it legal? For citizens of Residence-based Taxation countries at least, it is. Even Tax Office representatives admit that governments can’t tax individuals who are not tax residents in their countries. When Tax Offices try to scare its citizens by going after celebrities such as Shakira, they have to prove that they resided in the country for more than 183 days a year. We are not Shakira, though, we are not trying to cheat the authorities, pretending we live somewhere else. We actually live somewhere else, but nowhere in particular.

Theory VS Reality

As James Dale Davidson describes in its book The Sovereign Individual, The raison d’être of the nation state is to exercise its monopoly on violence to control the individual. Even modern democracies granting freedom to their citizens aspire to control them. You need to play by their rules if you want to do things such as getting married, having a child, applying for a mortgage or loan, getting a job, or even paying for a traffic ticket.

As Erich Fromm argued, the individual, while yearning for freedom, feels also the need of belonging to a group. That necessity takes her to submit to the dogmas of her society, including the role the individual is supposed to play. That applies to everything, from social customs to paying taxes.

Digital nomads are outliers in that scheme. They don’t abide by the rules of any country, and as such they are usually seen with that mix of admiration and resentment that Erich Fromm so appropriately described when talking about the newly found freedom of the individual during the Protestant Reformation.

On a more practical level, there’s no legal or fiscal jurisdiction that fully understands digital nomads. Even seasoned accountants have a hard time figuring out the situation of a location independent individual doing business and earning money.

However, I want to believe this situation will change. The nomadic lifestyle is being adopted by an increasing number of people every year. Initiatives like the Estonian digital nation are raising awareness of the fact that a lot of people are not tied to a country anymore.

Conclusion

In this article, I talk about how to avoid taxes legally in the context of digital nomadism. This is a very controversial topic that always leads to heated argument. While I agree that members of a society have to contribute to maintain the social benefits they are enjoying, in this post I discuss the situation of digital nomads, which is a completely different story.

Comments ()